One spring when Elizabeth Ham came from her home at Weymouth to Exeter on a visit to the Grey family she stayed at Haven Bank, the new house that had been built for them ‘on a small Knoll on the banks of the river opposite the city, which towered upwards from the water’s edge, crowned by its beautiful Cathedral. There was then no other dwelling near and the towing path the only thing between us and the river. Often on a calm evening Anne Grey and I used to amuse ourselves by answering to conversations that were borne to us from some street in the City, secure from detection even when our words were distinctly replied to.’

Her friends took Elizabeth on a couple of excursions, one of them to Powderham. ‘We went in one of those open, cane-bodied Sociables then in fashion and a very pleasant drive we had.‘ Crossing the ridge of Haldon, they arrived at Mamhead, seat of the earls of Lisburne, where the housekeeper received them. From there the three girls – Mary Grey, Betsey Grey and Elizabeth Ham – ‘set out for a walk to Powderham Castle, then the seat of Lord Courtney.‘

Elizabeth was probably familiar with the third viscount’s appearance from his visits to Weymouth with his sisters during ‘the season’ when king George III was in residence. ‘When they did not go to the Theatre, the Royal Family always walked on the Esplanade till dusk. Of course this was the grand promenade of the day; everyone dressed to the extent of their means, and a great many beyond it.‘

William ‘was the last of that branch of the family, and, I think, of ten children, all the rest girls. From the fair and delicate appearance of His Lordship, and from the circumstances of his being always seen with his sisters, and never with any gentlemen, I wove my own romance about him, and set him down to be really a daughter too. He or she lived mostly, and died, abroad. The sisters were all very beautiful.‘ […]

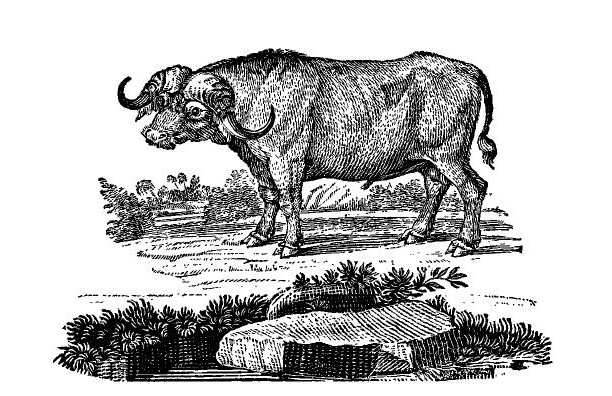

‘It was a very warm day but we enjoyed our ramble through the beautiful Park and grounds nevertheless. There were some Buffaloes in the Park but they did not frighten us. It was there I first saw the China or monthly rose growing in the open air. It covered the whole front of a beautiful Pavilion and was in full flower. I thought I had never before seen anything so pretty. […]

‘We went from Powderham to a Farm-house some three or more miles off, where we were to meet Mrs. Grey and dine. We were sadly tired and after dinner stole away to a hayfield, where we laid ourselves on the dry hay and had a good sleep. We were so refreshed by our nap that, after tea, nothing would serve us but a walk to Dawlish, some three miles farther. It was then a quiet, secluded little watering place. When we returned to our party it was time to start for Mamhead House, which place we left the next morning in the old Sociable.’

Elizabeth’s excursion took place around 1800, some time between the battle of the Nile in 1798 and the treaty of Amiens in 1802. When the short-lived ‘peace of Amiens’ came to an end, Napoléon began to assemble l’Armée des côtes de l’Océan (Army of the Ocean Coasts) for an invasion of the United Kingdom. The large camp at Boulogne with its associated flotilla could be seen from the south coast of England.

This new threat prompted a revival of the volunteer associations which had been formed in the previous decade. English volunteers were generally organised by their ‘hundred’, an old administrative grouping of parishes and division of counties. In Devon, Exminster hundred reached northwards as far as the village of Ide and southwards beyond Powderham down to Dawlish and Teignmouth on the coast.

William was appointed lieutenant-colonel commandant of the Loyal Exminster Hundred Regiment of Volunteers with William Rainsforth as major and Thomas Choron as ensign. Rainsforth was a professional soldier who had served as a British officer in north America. The Exminster volunteers met for reviews and parades, training exercises and sham battles with other associations. Queen Charlotte viewed the corps when it was encamped in Dorset at Maiden-castle. She noted in her diary that the men’s uniform (designed perhaps by William) was ‘Blue & Yellow & Silver, & their Caps or Helmets Black with Scarlet Ribbons or Feathers.’ In 1802 the loyal association won a silver medal for excellent shooting but in June 1808 their firing was distinctly less successful.

‘The following circumstance occurred with the Exminster Volunteers, on his Majesty’s birth-day. The regiment having paraded in Powderham Park, Devonshire, under the command of Major Rainsworth, received their ammunition, and were then marched on the hill near Lord Courtenay’s Belvidere for the purpose of firing three vollies, which should “make the welkin resound.” The muskets were primed and loaded – the word was given to make ready! — present! when one of the privates exclaimed, “Sir, we have got no flints.” On this an examination took place, and it was found that not a single man had a flint in his musket, the hammers being merely charged with a small piece of wood. What was to be done? the flints were locked up in store in the Belvidere, the person who kept the key was not to be found, and the door could not be forced. Under these circumstances, the Commanding Officer thought it proper to take the only step which prudence could dictate, and that was, to order every man to draw his cartridge, and throw the priming from the pan; which being done, the regiment then went through the motions, and reserved the real fire for a future opportunity.’

That item was presented as part of a ‘Feast of wit‘ for readers of ‘The Sporting Magazine; or Monthly Calendar of the Transactions of the Turf, the Chase, and every other Diversion interesting to the Man of Pleasure, Enterprise and Spirit.‘ It was not the first time that lord Courtenay’s belvidere had appeared in the pages of the magazine. A few years earlier, in the autumn of 1804, it had featured in an article by ‘T. N.’: ‘A ramble from Exeter to the Back-waters and Exmouth, with a return to Chudleigh.‘ This was published in two parts, with the first part entitled ‘The Toxophylites‘.

‘A band of Western Bowmen had obtained permission from Lord Courtenay to come with horn, and with hound, to hunt the deer for a whole day, on any part of his Lordship’s domain, from Exmoor to Exmouth; and, if they should kill the stag in the right Robin–Hood stile, the game to be dressed at his Lordship’s expence, and served up at the Star-cross Tavern, and the archer who struck the venison to death should be master of the feast. This company of merry Toxophylites overtook me in my way towards Powderham Castle, between Exminster and Kenton; they were all on horseback, richly dressed in their uniforms, and completely equipped with bows and with arrows. The Captain of the band was singing the old ballad of Merry-Sherwood, and all the rest joined in the burthen of the song. I kept pace with these jolly sportsmen for near a mile, and then turned off towards the sea-bank, opposite Topsham, wishing to make myself acquainted with the manner of admitting vessels of commerce to the Back-waters of Exeter, so much and so justly the boast of that city.

‘There were about thirteen ships waiting within the bar for the tide to carry them to the flood gates of the canal, when the craft with the trade from London claimed their right to be first admitted. This commodious, and charming aqueduct, is near four miles in breadth. The toll is paid at the entrance, to a fraternity called the Chamber of Exeter, under whose government the whole is regulated, and kept in perpetual repair. With the help of locks, through these waters, the trade is conducted with great speed and safety. […]

‘From the lower mouth of this canal, I passed the Broad-waters of the Ex, and landed at Topsham, a long straggling street, chiefly inhabited by fishermen, and others engaged in navigation and commerce; it is exceedingly ill paved, and most repulsive to the tender feet of indulgence.

‘Topsham is a place which has little or nothing to recommend it; for, excepting their females, their French brandy, and their fish, the people have nothing to tempt a traveller for one night to rest among them.

‘However, on quitting Topsham, the scene changes, the traveller is again put in spirits by a foot-road, and a grand variety of charming objects through a long chain of villages to the sea. Georges Clyst, Woodbury, and Limpstone, have much to recommend them; they are the foot-ways of health, and the lands of fertility.’

Lord Heathfield, a descendant of the Elizabethan mariner sir Francis Drake, lived near Lympstone at Nutwell but the rambler passed this house without comment: he had, it seems, confused both Walter Raleigh with Francis Drake and Withycombe with Widecombe where he expected to find ‘an ancient mansion‘ of the Drake family. Before arriving at Exmouth he extricated himself from this tangle with a bold patriotic flourish in honour of Drake: ‘Yes! while the British flag rides triumphant, and with untarnished splendour, around the repulsive shores of his unconquered country.’

‘We now rise to the high grounds of Exmouth, one of the pleasantest summer retreats on the southern shores of England; and where the rationally polite may find every accommodation to the height of their wishes.

‘Respecting sea-bathing, here is the clear, the uncontaminated saline. Thanet, Brighton, Bognor, have their charms, but Exmouth has those serene delights most engaging to a susceptive mind. Quiet, mingling with commendable pleasures, are at all times of the season to be found; and cheerful health, in her spray-washed sandals, constantly frequents these samphire covered cliffs.

‘—Many ravishing objects are seen from the high lands of Exmouth. The perforated rock below Dawlish, when the sun has passed the meridian, is a fine picture of rude nature, as is my Lord Courtenay’s park and castle of polished art. To the northward, the Cathedral church of Exeter rises majestically grand in the landscape; and to the eastward, that rapidly declining specimen of Saxon magnificence, Corfe Castle, terminates the view. Governor Paulk’s pillar, and my Lord Courtenay’s look-out, are pleasing objects; but the most brilliant of the whole is the British Channel, when the blocading squadrons shew themselves on the aquatic horrizon: while the commerce of England, outward bound and returning from many parts of the world, contribute to awaken a sensation not easy to be described; and at the close of day to behold the surrounding beacons is a spectacle awfully grand.

‘Descending to the beach, I hailed a fisherman returning to Topsham, who, for one shilling, landed me at Lord Courtenay’s park and gave me a fine pair of soles into the bargain: having a recommendation to view the internal beauties of this celebrated mansion, I presently entered Powderham castle. […]

‘From whatever point we behold the castle of Powderham, it exhibits a fine silvery feature in the landscape, insomuch, that it has been improperly called “The Lily of the Vale.” The front towards Exmouth has been considerably enlarged, after a modern fashion, and opens to one of the finest sheets of water in the universe; but the greater part retains its ancient consequence, its narrow windows, Norman battlements, peep-holes, &c.

‘In one of the largest and loftiest rooms of the castle his Lordship has several fine pictures; among the best, I observed the Tribute Money, by Rubens; Charles the first and his Queen, by Vandyke; Mr. Montague in his Turkish habit, and a very fine picture by Schnieder; over the chimney piece, in a most supurb frame [sic], Lord Courtenay, by Cosway; with some good shipping, and several pieces of less eminence. While I was here, I had a transient view of the three sister Sylphs of the castle; the first, like St. Cecilia, was playing on her harp: the second, like Ariel, singing to the divine harmony of the chords; and the third, like Penelope, employed in adorning the web of the loom.’

These ‘sister Sylphs‘ were probably Caroline, Sophia and Louisa Courtenay, the last three of William’s sisters to marry.

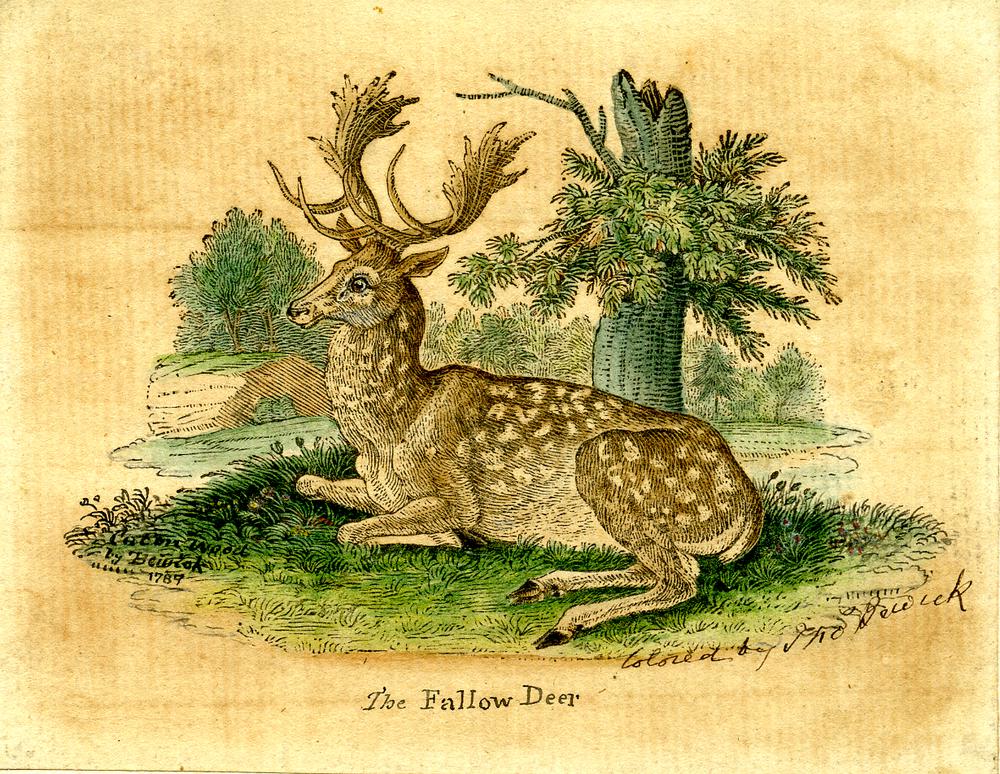

‘In quitting this palace of enchantments, I turned up the Park; and, having passed through a herd of mischievous buffaloes, and some of the finest deer in England, I was entering a fir plantation, on the brow of the hill near Kenton, when my ear was delighted with the sound of the spirit stirring bugle; the archers had struck the stag, and the poor trembling creature staggered feebly before me, I followed it to the valley where it fell; and the attitude of The stricken deer called to my recollection that charming description of the melancholy, Jaques, in Shakespear’s comedy, “As you like it.” […] The arrow that had pierced half deep between his ribs, bore upright its silvery fletch, and seemed to tremble at the cruel deed its point had done. […]

‘The Bugle again announced the triumph, and the Archers surrounded the expiring beast: he was presently carted and conveyed to Star-cross to have his haunches fashioned for the feast.‘

‘The beauties of the morning sky presently disappeared’ and in the afternoon a thunderstorm broke across the estuary but soon rolled away to the east. T. N. ‘left the shore with reluctance, and, after a most pleasant walk of several miles, arrived at Chudleigh, the seat of Lord Clifford, a place well worthy of the traveller’s attention.’ From that market-town he headed across the ridge of Haldon before coming down again into the broad valley of the Exe.

‘Descending through the villages, about night-fall, I passed St. Thomas’s, and, over the new and beautiful bridge, entered again the city of Exeter, and, not a little weary with this day’s exertions, set me down in ease at my inn, the White Hart, South-street, where the waterman I had met in the morning had conveyed my finny purchase; to which, with my landlady, I drew my seat, and finished one of the pleasantest rambles I had experienced since I left the metropolis’.

A few months earlier another stag had been killed at Powderham with a good deal less revelry and merriment. In his old age Henry Thomas Ellacombe, vicar of the Devon parish of Clyst st. Mary, recorded the episode, and Eliezer Edwards used this account in his Words, facts and phrases to explain the phrase ‘Getting into a scrape‘:

‘The deer are addicted, at certain seasons, to dig up the land with their fore feet, in holes, to the depth of a foot, or even of half a yard. These are called “scrapes.” To tumble into one of these is sometimes done at the cost of a broken leg; hence a man who finds himself in an unpleasant position, from which extrication is difficult, is said to have “got into a scrape.” ‘- Newspaper Paragraph. The Rev. H. T. Ellacombe, M.A, in ‘Notes and Queries,’ Feb. 14, 1880, says that in 1803 a woman was killed by a stag in Powderham Park, Devon. “It was said that, when walking across the park, she attempted to cross the stag’s scrape,’ which he says is ‘a ring which stags make in rutting season, and woe be to any who get within it.’ He confirms his story by a copy of the parish register, which records that ‘Frances Tucker (killed by a stag) was buried December 14th, 1803.’

Charles Palk Collyns had given a different version of this story in his Notes on the chase of the wild red deer (1862). Ellacombe had been born in 1790 at Alphington, not far from Powderham, and may have heard of the incident as a teenager, while Collyns had been born in 1793 at Kenton, even closer to the castle, and was familiar as a child with the deer-park nearby.

‘When quite a lad, I remember a stag in the park at Powderham in Devonshire, the seat of the Earl of Devon, that was a terror to all the boys and girls who occasionally passed through the park; and more than once have I climbed a tree, and remained there for several hours, in order to escape him. I also witnessed his death, after a most melancholy occurrence, which was as follows:

‘Fanny Tucker, a pensioner of the then Lord Courtenay, was daily employed to carry corn across the park to an aviary. “Old Dick,” for by that name was the deer known, knew her time of passing so well, that he almost always placed himself in her track, and received a handful of corn as she went along. It happened one day that the ill-fated woman was earlier than usual, and the deer was not at his post, but on her way back he made his appearance. Alas! she had reserved no corn for Old Dick, and enraged at this, he pierced her through with his horns, and killed her on the spot. Lord Courtenay, of course, had the deer at once destroyed. In the parish register of deaths, the reader will find the following entry:- “1803, Dec. 14th, Frances Tucker, killed by a stag.” A stone in the churchyard also calls the attention of the passer-by to the cause of poor Fanny’s death.‘

There is no possibility of misidentification here: Collyns certainly knew a red deer when he saw one, but the introduction to his story makes it clear that ‘Old Dick’ was a solitary specimen.

‘I know, from experience, that the stag, when he is confined in parks, and has no companion of his own breed with him, is a most dangerous customer, and would advise those who desire to keep the red deer, never to do so unless they have a herd of them.’

Perhaps the red deer and the buffaloes were gifts, or mythical beasts; perhaps there had been an intention to diversify the stock of cattle in the park by introducing these species. Or, as red deer roam widely, perhaps a group had come down from the moors to Powderham of their own volition as happened about that time at Boringdon, some miles to the west in the parish of Plympton st Mary, where some red deer ‘entered this park a few years ago, and remained with the fallow deer during several months.’ Nor were buffaloes unknown in Devon: in the 1830s Timothy Liveridge Fish kept a couple of them in the grounds of Knowle-cottage at Sidmouth. Perhaps those seen earlier at Powderham had been procured by sir George Yonge during his brief tenure as governor of the Cape Colony from 1799 to 1801.

Whatever the truth of the matter, William Craig Marshall showed neither red deer nor buffaloes in his watercolour painting from around 1800 but groups of fallow deer are pictured grazing peacefully in the park where their offspring can still be seen today from the Exe estuary trail or through the windows of passing trains.

###

- Extracts from Elizabeth Ham‘s autobiography, edited by Eric Gillett, were published in 1945 as Elizabeth Ham by Herself 1783-1820. Born in November 1783 at North Perrott in the English county of Somerset, she lived as a young woman for several years in Ireland with her family before returning to England where she became a governess, a unitarian and an author. Her novel The Ford family in Ireland was published anonymously in 1845. Elizabeth died in Somerset at Wick-house, Brislington in March 1859.

- The lines for Jaques come from act 2, scene 1 of As you like it.

- John Harvey wrote a ‘Guide to illustrations and views of Knowle Cottage, Sidmouth; the elegant marine villa orné of Thos. L. Fish, esq.’, but this account was given by Theodore Hands Mogridge: ‘The Grounds, about ten acres in extent, have the appearance of a small park. Scattered around are many figures on pedestals, and some foreign animals, whose habits of gentleness admit of their roaming about free and unshackled; among them are Kangaroos, Cape Sheep, two small Buffaloes, Pacas or South American Camels, and several varieties of Deer. Among the Birds are Emews or South American Ostriches, Black Swans, Pelicans, Macaws, Crown and Demoiselle Birds, Gold and Silver Pheasants, Grey Parrots, Peruvian Cockatoos, Paroquettes, &c. with a great variety of small foreign birds in the aviary or in cages.’

- The reference to sir George Yonge was added on 21 August 2022.

- In 1803 the engravings from William Craig Marshall‘s two views were published in The Beauties of England and Wales with this note: ‘The annexed Prints were engraved at the expence of Lord Courtenay, who generously presented them to this Work. The nearer view of the house from the park, represents the east front, with a large square tower in the centre, and the new music saloon in the north wing. The other view is taken at some distance, looking across a bay of the river Exe, and is intended to show the situation of the house, with the outline of the country, &c.‘ Perhaps William himself presented a pair of the prints to king George III for his collection. Marshall’s original watercolours still hang at Powderham-castle.

###

Images (from top):

- Thomas Girtin (1775-1802), Rainbow on the Exe, 1800. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Gilbert Davis Collection | Courtesy of the Huntington Art Museum, San Marino, California. | https://emuseum.huntington.org/objects/1719/rainbow-on-the-exe;jsessionid=DB31BCC71348EC804EFD014CCAB072AF

- John White Abbott (1763-1851), a view of Exeter from the towpath by Haven Bank.|http://francistowne.ac.uk/collection/list-of-works/a-view-on-the-haven-banks-of-part-of-the-city-of-exeter

- Lithograph by Charles Étienne Pierre Motte (1785-1836) after drawing by Victor-Jean Adam (1801-1866), Napoléon distributing the Légion d’honneur at the Boulogne camps, August 16, 1804. | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Premiere-legion-dhonneur.jpg

- Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), The Fallow Deer, British Museum, © The Trustees of the British Museum. | https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1882-0311-2155

- Thomas Girtin (1775-1802), Exeter from Trew’s Weir, c.1799. | https://rammcollections.org.uk/object/32-1956/

- Drawn by William Craig Marshall and engraved by William Angus, Powderham Castle &c., Devonshire, 1802. | http://george3.splrarebooks.com/collection/view/powderham-castle-c.-devonshire.-engravd-by-w.-angus-from-a-drawing-by-w.m.-

- Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), A General History of Quadrupeds | The Buffalo, 1790.

- Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), The Red Deer, British Museum, © The Trustees of the British Museum. | https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1882-0311-2164

- Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), A hind and a stag of the family of Red-Deer and a Fallow-deer. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark. | https://wellcomecollection.org/works/h3egzy39

- Drawn by William Craig Marshall and engraved by Benjamin-Rodolphe Comte (1760 or 1762-1851), Powderham Castle, Devonshire, 1802. | http://george3.splrarebooks.com/collection/view/powderham-castle-devonshire.-engravd-by-b.-comte-from-a-drawing-by-w.m.-cra

- George Rowe (1796-1864), drawn from nature & on stone, The grotto and jet-d’eau, Knowle Cottage, Sidmouth. | https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/knowle-the