“I have received with much pleasure your letter on my two Gazettes Extraordinary as your Lordship very aptly styled them.”

(John Wilkinson to the viscount Courtenay, Tuesday 18 May 1824)

Although he had visited William viscount Courtenay in France at the château de Draveil a couple of years before, it was not until the spring of 1824 that John Wilkinson had a chance to visit Powderham-castle, William’s birthplace in the English county of Devon. An attorney based in London, he had taken on overall responsibility for William’s affairs in England and Ireland from the viscount’s cousin Henry Wrottesley.

Ten years younger than William, Wilkinson had grown up in the Yorkshire market-town of Skipton where his uncle James, a mercer, traded in cloth. After James Wilkinson died in 1807, John had moved to Leeds where he trained as a clerk of James Nicholson to become an attorney. This arrangement was made by “my dear relation and friend”, his older cousin John Parkinson, the sole executor of their uncle James’s will.

Born at Winterburn in the parish of Gargrave, John Parkinson was already in practice as an attorney in London where his younger cousin soon established himself too, with an office in Southampton-street. After a few years, John Wilkinson became in 1819 a partner of Thomas Smith and John Lake, with chambers in New-square at Lincoln’s Inn. In April 1821 he made a journey back to Yorkshire in order to marry his cousin Margaret Wilkinson in the parish church at Gargrave.

Returning to London, they took a house in Bloomsbury at 58 Burton-crescent (now known as Cartwright-gardens) where they lived for more than twenty years. At the time of these two letters only Margaret, the first of their four children had been born, although Ellen was soon to follow in December 1824. As a widow, Margaret Wilkinson moved back to Yorkshire with her children, dying in 1848 at her home in Clifton, York. She was buried at Gargrave while her husband who had died in 1845 at their later home, 40 Tavistock-square, was buried in London at the cemetery in Kensal Green.

John Wilkinson continued to work as William’s attorney until the viscount’s death at Paris in 1835 when he became an executor of William’s English will. These letters, sent to the viscount Courtenay at the château de Draveil, have been transcribed from the law-firm’s copies which are now held in the archive at Powderham-castle. My thanks to Katie Cormack and Charles Courtenay for photographs of the letters and permission to use them. Copyright of the letters belongs to Charles Courtenay, Earl of Devon.

“My Lord, I fear you will think it long before you hear from me, but I did not in fact return from Devonshire sufficiently early to write by the packet of last week.

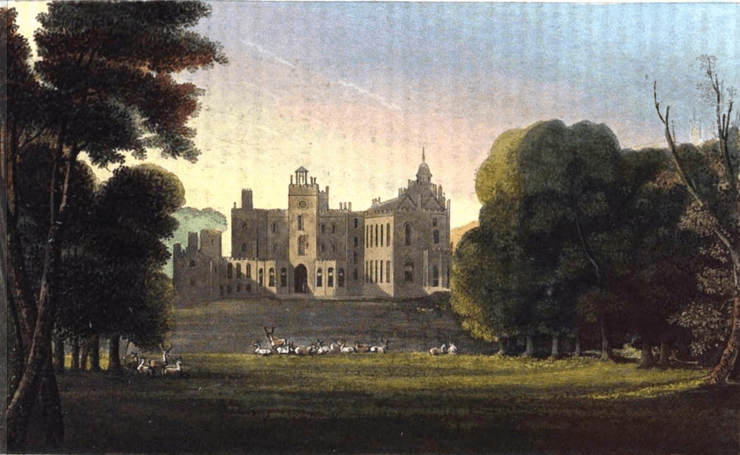

I feel the greatest pleasure at being enabled to inform your Lordship that I found every thing (with some trifling exceptions which I shall notice by and by) in the most perfect order. The external appearance of the castle and the grounds around it was such as to leave no room for improvement and far exceeded my utmost expectation. On entering the interior, one cannot but be instantly struck with the alteration occasioned by the sale of the furniture, but even this is far less striking than might have been expected and the admirable state in which all the apartments are kept by Mrs. Bush tends greatly to compensate for the loss of the furniture. Although Mrs. Bush may be said to be doing no more than her duty and that the impulse of self interest must naturally operate as an incentive to exertion, still I do not feel that I should be doing this woman justice were I, on this occasion, to withhold expressing the gratification I derived from observing the result of her superintendence and management.

Passing from the castle to the garden I enter into another person’s jurisdiction, and that person I know is no favorite of your Lordship’s. If I may be permitted however to express an opinion, as to the mode in which he discharges his duty from the observations I could make, I should say that there cannot be much, if any ground for complaint at present.

I am a great admirer of plants but do not profess to be any judge as to their merits or particular claims for admiration. I can only say that Hall has an amazing large collection and according to my notions a most beautiful one. I certainly never saw any to equal them. Mr. Clack says the collection has latterly been much improved and that Hall manages the plants and the gardens much better now than he did.”

Both the housekeeper and the gardener held their post for several years more. William granted an annuity to Anne Bush by his English will and she retired to Dawlish on the coast a few miles to the south of the castle. She was living in the resort at the time of her death in 1839 at the age of 80. Anne’s husband had died before May 1835 – he may have been the Thomas Bush buried at Powderham in 1828 aged 64 – and all her property passed to a widowed daughter and her four daughters.

Born at Stowford in the west of Devon, William Hall became a gardener in the Plymouth area where he married Mary Pocock in 1812 at Stoke Damerel. The first of their four children was baptised at Powderham in 1813. Although from May 1833 it was ‘Mr. John Parr’ who was identified as ‘gardener to the Earl of Devon‘, ‘Mr. Hall’ from Powderham was winning prizes at exhibitions of the Devon and Exeter Botanical and Horticultural Society until August 1835. Some time later Hall moved to his wife’s Devon home town of Ottery St. Mary, becoming a maltster at Yonder-street before retiring to Exeter after Mary Hall’s death in 1843. He moved again a few miles south to the coast, dying aged 80 at Budleigh Salterton ‘after a long illness‘ in 1857.

The fifth son of Bridget and Thomas Clack, Edward-Robert Clack (1786-1855) was one of William’s cousins. He accompanied William on his journey into exile, staying in New York from 1811 until 1814, but then returned to Devon rather than staying with William in France.

“From these gardens we went on to that delightful retreat in the plantation where I found every thing as regarded the plants and the grounds in as neat order as they possibly could be. I should much wish to see this place in a more advanced stage of the season, and when the plants and trees are in their full luxuriance. Should I have the good fortune to be again called upon to make another visit to Powderham I will if possible so arrange as to make it in the summer season or in the autumn. Nothing in my opinion could scarcely excel the beauty of the scenery as it displayed itself last week on the first budding of a tardy spring, but this must fall very far short of the appearance which a more ripened state of the seasons must throw upon it.

In the plantation garden I found that the outside wood and frame work of the green house and of the pavilion wanted painting; I therefore gave directions for this being done. I also directed the two entrance gates at each extremity of it to be painted. The temple also requires some repairs, and indeed a new covering. I did not however order this to be done until I had previously communicated with your Lordship on the necessity and as to your wishes on having it kept up. It really seemed to me that it might very well be spared as in the summer season the thick foliage of the lower branches of the trees surrounding it must almost exclude it from the view of any one. If it is pulled down the wood work may be preserved and as the building is but of a slight and temporary nature it could at any time and at no great expense be put up again. Will your Lordship be kind enough to let me know what you would wish to have done respecting it.

Were I to note every observation that occurred to me on going over these beautiful grounds I might continue writing for a week. I must therefore content myself for the present by selecting those which appear to me to be most deserving of communicating.

The noble range of new plantation at Melons [Mellands] must be pronounced by every one who sees it, and who remembers the ground before it was planted (which I do not) as a most striking improvement and addition to the grounds. With the exception of the upper part of the plantation (which partly from the exposed situation and thin soil and partly from the depredations of our old friends the rabbits is not in so thriving a state as I could have wished to have seen it) the whole is growing most luxuriantly and in some places begins to be greatly in want of thinning. I was much grieved however to remark the very serious injury done to the Scotch firs by another description of marauders than the rabbits viz the squirrels. There are scores and I may almost say hundreds of these firs completely destroyed by these animals which I saw running about in every direction. I did not hesitate giving the strictest injunctions I could to Wilcox and his brother gamekeeper to destroy them or at least to diminish their numbers which they assured me they would do. I also followed up the directions which had been previously given to them through Mr. Pidsley respecting the rabbits (of which there seems to be a very large colony) and to reduce their numbers also at a proper season. They promised strongly to do so but I thought of your Lordship’s anecdote of the duchess of Kingston.”

Abraham Wilcox had been a gamekeeper at Powderham since 1794, working alongside Richard and William Cornelius before he himself became the head keeper. Wilcox was assisted from 1815 by William Howe, another member of the suite which journeyed to New York with William on board the ship Jane in 1811. Like Edward-Robert Clack, William Howe returned to Devon rather than take up residence in France. After Wilcox died in 1829, Howe became head keeper but by 1836 he had moved across the estuary and was working as an alehouse-keeper at Exmouth where he died in that year. Although he married twice (firstly in New York soon after his arrival, then in 1826 as a widower at Powderham) William Howe mentioned no children in his will.

There was a story about the duchess of Kingston making an initial payment of £25,000 for the château de Sainte-Assise, not far from Draveil. “The purchase, on the part of the Duchess, was a good one. – There were not only game, but rabbits in plenty, and finding them to be of a superior quality and flavour, the Duchess, during the first week of her possession, had as many killed and sold, as brought her three hundred guineas [£315].“

“The plantation made (I believe since your Lordship left England) on the Starcross and Kenton sides of the marsh ground to the right of the castle is also in a most thriving state, as is also the one at Warborough and likewise such parts as have been newly planted on Kenton Common, the whole of which I went over.

The cutting of the timber is proceeding but I am sorry to say that we shall by no means realize so much money from the sale of it as I had calculated upon, although my calculation scarcely amounted to a third of that so thoughtlessly and injudiciously made by Mr. Clack. I fixed my calculation at about £8,000 on looking over the particulars of the timber when first sent up here. A great proportion of it however has unfortunately proved to be so seriously injured by a pernicious custom of the tenants lopping and paring the trees, so as to render them almost totally unfit for all purposes to which timber is usually applied. So that instead of raising near £8,000 I fear we shall not reach £6,000. According to the present estimate the sum will not be more than about £5,500 unless we go into the park, from whence I am satisfied we might extract from £1,000 to £2,000 without impairing in any degree the beauty of the scenery. This however with your Lordship’s permission had better stand over a short time, at least I recommend that nothing be done upon it until the present cutting is completed, for as the timber in the park is much more valuable than that which is now falling a better price must be demanded should you ultimately decide on selling any portion of it.

Mr. Clack had received your Lordship’s letter on his ceasing to have any thing further to do with the expenditure at Powderham and I flatter myself that I have succeeded in placing that business and the management as to the employment of labourers and delivery of timber on a most satisfactory footing. I saw more of Mr. Clack on this occasion than I had ever an opportunity of doing before, and although I found him to be a very worthy good sort of man yet I became most fully impressed with the conviction that he was, as your Lordship had expressed in your letters, totally unfit to superintend the management; that his easy temper, and as I may say want of mind and firmness, left him exposed to all species of imposition.

He seemed to consider the announcement of the change as coming suddenly upon him, but he expressed no disappointment at the measure and requested me to say that he should still consider his best services at your command, on any little occasion in which they might be deemed useful. I am thoroughly satisfied and so indeed he admitted, that the change will be a benefit instead of an injury to him, and that the additional £100 a year which he has had has by no means been equivalent to the increased expense which the situation led him into. I settled his accounts both as to the expenditure and his annuities and paid him a balance of £216, due to him on the foot of those accounts as up to Lady-day last. I hope this sum will relieve him from his engagements to his tradesmen and his landlady Mrs. Frost, but whether it will do so wholly or not I much doubt. I think he will go to Chudleigh and live with his sisters which must be clearly the most adviseable plan for him to pursue and with the joint income which they derive from your Lordship’s bounty they ought to live very comfortably.”

Edward-Robert Clack’s landlady was probably Ann Frost, a widow living at Blackheath farm, on the Powderham estate to the northwest of the castle. Her son John took over the running of the farm but did not marry until 1826.

There were three Clack sisters living together at Culver-street in the market-town of Chudleigh not far from Powderham: Elizabeth, Charlotte-Bridget and Mary-Ann. Edward-Robert shared a house with them until Charlotte-Bridget’s death in 1835. He had become blind by 1851 and died at the age of 69 in 1855. His elder sister Elizabeth survived him until 1859. Their younger sister Mary-Ann became a resident in 1842 of Bowhill-house, a lunatic asylum in Exeter; at the time of her death in 1864 she was living with her niece Harriet Holland in Okehampton.

“The new arrangement which, under the sanction of a recent letter I had the honor of receiving from your Lordship, I have made is this: that all the wages and pensions and bills of every description be paid monthly by Mr. Pidsley, so that all the expenditure will thus pass under his immediate notice and be subject to that very necessary check and control which such an expenditure ought to be subject to. The employment of the labourers, carpenters etc. and the delivery of timber for repairs I have placed under Mr. Rowden’s management – a fitter person I am confident could not be selected from the whole county of Devon. He succeeded his father as woodwarden on your Lordship’s estate at Moretonhampstead, as the father succeeded his father in the same situation. Thus the family have been employed three generations under that of your Lordship’s, and as the present man has been employed all his life in the management of timber, and is not a carpenter or engaged in any trade which might excite a suspicion of his being influenced by dishonest motives, he is in every respect (at least so it seemed to me) qualified to attend to this, one of the most important branches of the Powderham expenditure.

The consumption of timber in keeping up and repairing the fences seems at present to be immense, and must at any time and under any management be very considerable. Still the extent of this consumption must in a great measure depend on a judicious selection in cutting and in a proper application. Some more decisive measures must also be taken for the purpose of detecting those who in the most wanton and shameful manner steal the palings, and destroy and pull down the fences. This is not a new grievance your Lordship will say, but I am sure you will concur with me in saying that every means ought to be taken to suppress it, which I am satisfied is not the case at present, or at least has not been latterly. It constituted the only serious complaint I had to make on looking over the grounds, for I am convinced that unless the depredations were winked at by those who are eating your Lordship’s bread, they never could be committed to the extent they seem to be.

I left the strongest injunctions I could on this subject. But to return to Rowden and the terms of the arrangement made with him. As woodwarden at Moretonhampstead he has 30 guineas a year and he has also had £10 per annum for looking after the Whitstone woods, which are now becoming very productive, these together making about £40 per annum. As he must necessarily be three or four days in the week and frequently more at Powderham, it follows that the whole of his time will now be taken up in your Lordship’s service, and the distances between Powderham, Moreton and Whitstone also render it necessary for him to keep a horse. I therefore did not consider it unreasonable to make an addition of £40 a year to his allowances thus fixing his total salary at £80 per annum without any allowance whatever on account of diet, only finding his house provender whilst at Powderham. When at Powderham he will sleep in one of the rooms over the stables where he has slept during the time that he has been engaged in the measuring and cutting timber and Mrs. Bush will dress his meals for him. Fortunately he has no engagement at Moreton to prevent his spending so great a portion of his time at Powderham, for he has lately lost his wife, and has given up the management of his little farm to an only son.”

John Pidsley (1763-1840) had been the agent for William’s estates in Devon for some twenty years. At the end of 1810 he had accompanied the viscount from Powderham to Bridgwater in Somerset, the first stage of William’s journey into exile. Pidsley had trained as an attorney with John Stoodley in Exeter. In 1789 he married Marianne Salter at Clyst St. Mary, a village to the east of the city. Together they had six children but only Elizabeth and Marianne survived their parents. John Pidsley died a widower in February 1840 at his home in Paul-street, Exeter, and was buried at Clyst St. Mary.

John Rowdon (1774-1829) was born in Moretonhampstead where he married Dorcas Jackson in 1798, a year after the death of his father. The couple had two daughters and a son John who took on the farm at Harcott before becoming the fourth Rowdon to act as woodwarden for William’s family. Dorcas died six months before Wilkinson’s visit and in 1825 John married Hannah Wilcox whose father Abraham was gamekeeper on the Powderham estate. Both John Rowdon and his father-in-law died in March 1829 ‘from the inclemency of the Weather being exposed in the Marshes all night‘.

“With the management of the gardens and the arrangement made with Hall two years ago as to them and the preservation of the shrubberies and walks around the castle I have not interfered with. As respects the preservation and appearance of all these things I am convinced any alteration would be no improvement. As to the terms on which Hall holds the gardens I can scarcely venture to express an opinion about them. The rent he pays is certainly a mere nominal one, but the expense of keeping up the different hothouses etc. etc. must be very great, and if it be true as Mr. Pidsley informs me it is, that almost all the surrounding gentry in the neighbourhood of Exeter sell plants and the surplus produce of their gardens, the prices must naturally be so diminished as most materially to affect any profits Hall may make. It will therefore be worth consideration whether it may not be better to acquiesce in the present arrangement on this head than by disturbing it place the matter in a state of uncertainty and difficulty as to management.

That I may not completely exhaust your Lordship’s patience I will conclude what I have to say in consequence of my recent visit into Devonshire in a further letter to morrow and shall only add now that I despatch by this evening’s mail a deed for your signature in which will be found a note explaining the purport of it.”

The following day’s letter is transcribed at Gazette extraordinary #2 | Wednesday 5 May 1824.

Images (from the top)

- Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), The squirrel, wood-engraving, illustration to Ralph Beilby’s ‘A General History of Quadrupeds‘, Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1790. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1882-0311-2278. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), [squirrel], wood-engraving, tail-piece to Ralph Beilby’s ‘A General History of Quadrupeds‘, Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1790. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_2006-U-1629. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- John Gendall (1790-1865), ‘Powderham Castle | The seat of Vist. Lord Courtenay‘, aquatint, ‘The repository of arts, literature, fashions, manufactures, &c‘, London 1 April 1825, page 192.

- Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), The rabbit, wood-engraving, illustration to Ralph Beilby’s ‘A General History of Quadrupeds‘, Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1790. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1882-0311-2276. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- John White Abbott (1764-1851), Chudleigh, Devon, pen ink and watercolour, 1818, Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery.

- John White Abbott (1764-1851), Powderham, Pen and sepia ink, 1808, © Copyright Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery and Exeter City Council. RAMM Collections.

Page history

- 2024 April 12: first published online.