“I have received with much pleasure your letter on my two Gazettes Extraordinary as your Lordship very aptly styled them.”

(John Wilkinson to the viscount Courtenay, Tuesday 18 May 1824)

________________________________________________________

On Tuesday 4 May, along with the first of his two ‘gazettes extraordinary‘, John Wilkinson had sent William a much shorter letter about restructuring one of the viscount’s many debts (£4,000 to William Cockburn, dean of York). ‘The effect of this arrangement will be that during the remainder of your Lordship’s life, you will have to pay in respect of this transaction £200 a year instead of £400. It is astonishing to me that such an arrangement was not years ago carried into effect.’ On the next day he returned to the report of his observations after visiting Powderham-castle in the later weeks of April.

Several people are mentioned in both of these long letters: brief notes on Edward-Robert Clack, Anne Bush, John Pidsley and John Rowdon are included at Gazette extraordinary #1.

“My Lord, I commence today under the expectation that I cannot have a great deal to add to the very long, and what I am apprehensive your Lordship would consider very tedious communication which I had the honor of making to you yesterday but when I once begin there are such a variety of matters which occur to me as fitting to be mentioned that it is difficult for me to say when I shall finally conclude.

On looking over Mr. Clack’s accounts I was much struck with the very large quantities of oats and wheat which appeared to have been purchased and consumed. It will perhaps be better that I should reserve for the opportunity of a personal communication with your Lordship the observations which arose to my mind on this subject. The pheasants I was told were large claimants on the granary. I will not stop to enquire into the necessity of their being permitted to be so, but admitting the fact, I suspect that more domestic descriptions of the feather’d tribe share, along with the pheasants, the hoards of the granary. I have no doubt indeed of the fact and I really do not know how we can prevent little misapplications of this kind. To expect perfect honesty in all those retained on the establishment would be indulging in an expectation which every day’s experience of the foibles of human nature tells us we ought not for a moment to entertain. Evils of this description in cases of this kind must therefore be submitted to, and all that can be done is in every flagrant instance to reprehend and check them as much as possible.

Another considerable claimant on the granary was stated to be a very near neighbour of Mrs. Bush’s – a native of some part of France and sent over to Powderham as Mr. Clack informed me, by your Lordship. Poor Mrs. Bush supplicated most earnestly for the removal of this despoiler of the sweet air and delightful breezes that would otherwise play around her newly fitted up apartments. In summer she describes the nuisance as most intolerable and I am sure it must be so. Allow me my Lord to add my supplications to those of Mrs. Bush’s for the total removal of this arrival. He will assuredly some time or other be doing some mischief, for he is savage beyond all conception; pray let him be destroyed, and let us thus rid Mrs. B. of her nuisance and your Lordship of a most unnecessary and no inconsiderable expense for, independent of the corn and other articles he must consume, the straw of a good farm must be required to furnish him with bedding.

I found one of the windows of the belvidere in so bad a state of repair that I ordered it to be sent to Exeter, the workmen at Starcross not being considered equal to the task.

The sea wall appears to have been well and effectually repaired and I trust will stand for a long time without requiring any thing considerable to be done to it.

The Courtenay Arms at Starcross is undergoing a thorough cleansing as to painting and papering. The painting had begun as I was there, as I had directed in consequence of previous communications from Mr. Pidsley, and when I saw the rooms I ventured to order the papering which in some places was getting into very bad condition and would have looked extremely shabby after the new painting.

The project for building a chapel at Starcross is still warmly entertained and from the contributions the active promoters of it had obtained from the government committee and from some charitable institutions there seems little doubt but that the measure will be proceeded with and carried into execution. Your Lordship I understand had been apprised of the business, and had given your sanction for the appropriation of a piece of land for the site and for the small endowment which is necessary. We looked at a small field on the right hand side of the present road leading out of Starcross towards Dawlish which is considered and indeed appears to be a very eligible situation. It will be on the left, and front or nearly so on one side the proposed variation of the road out of Starcross towards Dawlish which will give it a remarkably good entrance and access.”

The sea wall may have been damaged in the storm of December 1821: ‘The gale and the tide were both at their height at ten o’clock, when the sea broke over the wall into Starcross, filling the street to a considerable depth. […] The lower road from Powderham Church to the second Marshgate, is impassable; and the mischief done thereto, and to the river wall, cannot be repaired but at a very considerable expence.‘ Another storm in November 1824 was to bring more destruction and loss of lives along the southern coast of England.

The Courtenay Arms at Starcross became a venue for balls in winter, public breakfasts before the summer regatta, and meetings of the Chosen Friends’ lodge of freemasons.

In December 1827 Christopher Churchill Bartholomew was appointed as the first curate for the new Starcross chapel which was consecrated two months later by the church of England’s bishop of Exeter. A few days before Wilkinson’s letter the Western Flying Post carried an item on the proposal: ‘The establishment of a chapel in this situation will also provide, for the first time, a place of divine worship for the numerous crews of colliers who lie at anchor at a place called the Bight‘.

“Lord Rolle I fear is attempting to encroach on your Lordship’s rights in the river Exe, by claiming the soil or exclusive right of ballastage from two sand banks called the Shelley and Bull Hill situate in the middle of the river. I shall immediately investigate and ascertain the precise nature as far as I can of your Lordship’s title and rights. The simple question is whether the soil of these banks belongs to you in right of your manor of Kenton or to Lord Rolle in right of his manor of Exmouth. That you have the royalty or what may be termed the admiralty jurisdiction over the whole of the river and the exclusive right of fishery and netage, I understand is not disputed but it is contended as I hear on the part of Lord Rolle that you are not intitled to the soil of the bed of the river beyond the middle of the channel when running at low water.

It is singular but I find from the papers which Mr. Pidsley had collected from the office at Powderham, that this is not the first time the question has been agitated and indeed tried between your Lordship’s family and Lord Rolle’s. In 1736 a cause was tried at Exeter touching the right to the soil of a bank adjoining on Exmouth Point called the spit and claimed by your ancestor Sir William Courtenay, but the jury gave their verdict in favor of Lord Rolle’s ancestor, and in 1743 another cause was tried as two banks higher up the river called Shore Keys and Exmouth Bulls but which was also decided in favor of the ancestor of Lord Rolle. These are two discouraging circumstances on the present occasion but do not afford any thing conclusive upon it. The case however is by no means free from doubt or difficulty but whatever may be the result I do not see that your Lordship can well avoid disputing the claim now made, for at low water the western extremity of Bull Hill approaches very near to the Kenton side of the river running nearly parallel with the warren.

Possibly your Lordship may not remember the precise situation of these different banks of land (which are indeed frequently varying) or understand from my statement to what extent Lord Rolle is now pushing his claim. I shall therefore take an opportunity of sending you a sketch of them, so soon as I receive one from Exeter which I directed to be made, that my representation of the matter may be more intelligible.”

The manor of Exmouth lay on the opposite shore of the Exe estuary from Powderham and the manor of Kenton. John lord Rolle (1750-1842) had been a member of the Westminster house of commons before 1796 when he became a baron and a member of the Westminster house of lords; one of his houses in Devon was at Bicton (shown below).

“I went through and examined Mr. Pidsley’s accounts up to the year ending last Lady-day, but on which I will not trouble you with any particular detail at present as they can be much better discussed and explained in a personal interview. For the present therefore I shall content myself by observing that although the balance due to Mr Pidsley upon the year’s account being about £3,000, seems a large sum, yet it is altogether his own fault that it is so, for the arrears even up to Michaelmas last (since which time another half year’s rent has become due) are more than sufficient to discharge the whole of this balance, and therefore when we take this circumstance into consideration, and that all the interest and annuities with some exceptions (which I believe may be calculated as falling short of £1,000) have been paid as up to Lady-day last, I think I am fairly justified in stating – and it is with much pride and gratification I make the statement – that the Devonshire account stands remarkably well.

Dearly bought experience, my Lord, must have long since convinced you how impolitic and unwise it is to entertain expectations of too sanguine a nature, and similar experience has taught me that I shall best discharge my duty towards your Lordship by permitting events to speak for themselves, and not by misleading you, as I possibly might do, with prognostications and prophecies. All that I shall therefore now say on the subject is to express my hopes, that the arrangements which I made on my visit to Powderham will meet with your full concurrence and approbation, and also to express my conviction that if they are persevered in your Lordship must soon experience considerable relief and benefit.

Much, however – as indeed I may with truth say, every thing depends on your Lordship’s co-operation in following up these arrangements and in curtailing the expenses. Your Lordship ought to bear in remembrance, that your estates diminished as they have been whilst at the same time there has been a large increase of incumbrances, have to provide after discharging all interest and annuities, for the maintenance of two establishments instead of one as formerly.

Keeping this in mind I do hope that you will assist me in every way you possibly can in keeping down the expenses at Powderham, for without your cordial assistance I can do nothing. I gave the strictest injunctions on the subject both to Mr. Pidsley and Mr. Rowden. A compliance with these injunctions may and doubtless will expose them to the envy and malice of those who may feel themselves aggrieved by measures of economy. Representations and statements to your Lordship from these individuals will follow and every artifice attempted for the purpose of undoing what has now been arranged.

Your Lordship will excuse my anticipating all this, which I do, not as intending thereby to express any doubt or fear that you will listen or give credence to any such communications or send over any instructions in consequence of them, without previously making full enquiry into the circumstances and probing to the bottom the accuracy of any statements that may be made, because I am sure you will disdain to act on any such representations or to deal so disingeniously with myself and Mr. Pidsley, as to do so without such preliminary enquiry, but I take the liberty of anticipating all this for the purpose of shewing your Lordship what I am fully prepared to expect and also for the purpose of placing you on your guard.

Whatever may have been Mr. Pidsley’s bias towards Mr. Courtenay on former occasions, I think I may with great truth say, as I do with the most perfect sincerity believe, that no man can have your Lordship’s interest more at heart than Mr. Pidsley has at this time, and I also really believe (although I certainly had entertained some doubts on the subject previously) that he takes every pains to make the Devonshire property as productive as possible. I blamed him for allowing the arrears of rent to remain so heavy and told him that he did so to his own prejudice and I could not allow you to pay him interest on his advances which would not be necessary in case he made proper exertions to get in the arrears. This he admitted, and likewise that there was now no occasion to indulge the tenantry by permitting them to be in arrear with their rents, and added that he should call them in immediately, and repaid himself the advance he had made during the past year.

He has stated and settled the particulars of the account with Goodridge, who has made a payment of £200 on account and has been allowed for £200 for damages done by the rabbits. Mr. Pidsley thinks that Goodridge will now be able to continue in the management of the farm.

No answer has been received by Mr. Pidsley from Corbyn to the application for his arrear of rent and for the possession of the farm house. The former although very considerable I fear there is no hope of ever obtaining, but the latter really ought to be given up, as the withholding it is a serious inconvenience to the farm.”

William Courtenay (1777-1859) was a second cousin of the viscount and had been his heir presumptive since the bishop of Exeter died in 1803. Relations between the two men were strained.

A widower, Alan Goodridge (1758-1831) was farming at Melons (Mellands) to the north-west of the castle. In his letter of the preceding day Wilkinson had reported ‘a very large colony‘ of rabbits in the neighbouring plantation. Although not born in the parish, Goodridge was already living at Powderham when he married Mary Gotbed in 1797.

Henry Corbyn (1781-1855) had been the tenant at Marsh farm in South Town, Kenton. Born in Ashprington, he married Elizabeth Haydon in 1804 at Kenton and they had five children. He was a churchwarden at Kenton, and employed from 1810 as a hind at Powderham, responsible for the livestock on the estate. In 1821 Corbyn moved to Draveil, probably as tenant of the home farm on William’s estate. He witnessed a codicil to William’s will in June 1831 and stayed in France after William’s death, farming in Normandy with his son at the forêt de Gavray until 1843 or later. Elizabeth Corbyn was buried at Starcross in 1848 and Henry spent his last years in Ashprington where he died at the house of his married daughter Mary Moysey.

“On the plan of discharging the surplus balance due to Mr. Pidsley on the settlement of his accounts to Lady-day 1823 beyond what was secured to him by mortgage, but on account of which surplus balance I have paid £1,000, I shall have occasion perhaps to write to you in a short time.

At present I notice the matter with the view of observing for your consideration that part of my plan will be to propose that the wine at Powderham be sold during the summer at Exeter by samples. It is really a pity and a shame to allow it to remain decreasing in quality and consequently in value.

I think I have now touched upon every thing necessary for me to notice at this time and am etc.”

William’s response to the gazettes arrived at Lincoln’s Inn on Saturday 15 May, and was probably greeted with relief. He seems to have concurred with many, perhaps even all of the initiatives that had been put forward. John Wilkinson lost no time in writing to John Pidsley at Exeter.

“I have sincere pleasure in sending you the above copy of a letter received this day from Lord C., and which I think it best to send you as conveying distinctly and clearly his directions on several matters. I recommend you to postpone selling the wine until your adjacent watering places are filled with company, when, as of course the wine will be divided in small quantities, the number of competitors will be considerably increased and I have no doubt but that something considerable will be realized from this source.

I suppose you will consult with Wilcox and How as to the most adviseable method of destroying the boar. I need not say that it is desireable to carry the sentence into execution immediately and you will agree with me in the propriety of having it done as privately as possible, and of making as little noise about it as can be. I hope the keepers will exert themselves in destroying the squirrels and likewise the rabbits when the proper season comes round. […]

He seems to have a perfect recollection of the subject of the dispute with Lord Rolle and from what he says it would appear that even in his lifetime this is not the first agitation of the question, and on which it may be adviseable you should see Cartwright […]

What think you of getting Corbyn’s arrears from his wife? I only wish you may.”

Part of ‘the Powderham cellar of wines‘ was sold on 9 August ‘in small lots for the accommodation of private families‘. According to newspaper reports ‘from the known excellence and age of the wines, there was a large attendance, and high prices were obtained.‘ Around the same time William’s library was shipped from Powderham to France.

There are brief notes on Abraham Wilcox and William How in Gazette extraordinary #1. Robert Cartwright (1773-1832), steward to the Palk family at Haldon-house, had earlier been steward at Powderham-castle in the years before William went into exile.

More than four hundred of John Wilkinson’s letters have survived in the volume of copies at Powderham-castle. They date from 9 December 1823 to 28 September 1825. Many were addressed to the agents for William’s estates in Ireland and England: Alfred Furlong at Newcastle (County Limerick) and John Pidsley at Exeter (Devon). There are another seventy-five letters addressed to William himself. These not only deal with legal matters (such as leases, codicils, annuities, rent reductions, debts and delapidations) but also with items that William had requested be sent to him in France: linen shirts, barrels of oysters and a lavishly illustrated publication on the coronation of king George IV among them. Copyright of the letters belongs to Charles Courtenay, Earl of Devon.

Images (from the top)

- Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), The wild-boar, illustration to Ralph Beilby’s ‘A General History of Quadrupeds‘, Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1790. https://www.porkopolis.org/pig_artist/thomas-bewick

- Thomas Bewick (1753-1828), [squirrel], wood-engraving, tail-piece to Ralph Beilby’s ‘A General History of Quadrupeds‘, Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1790. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_2006-U-1629. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

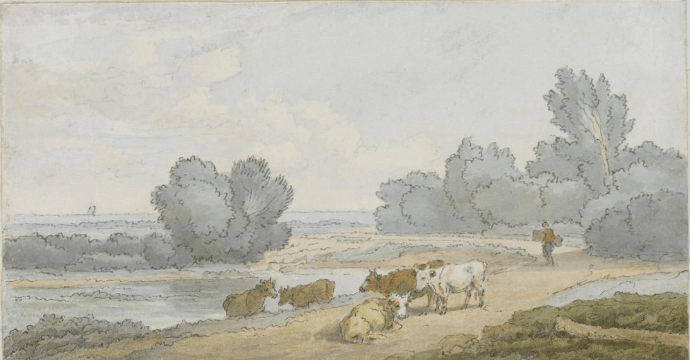

- John White Abbott (1764-1851), ‘On the Warren, Kenton, Devon‘, 1826. Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery.

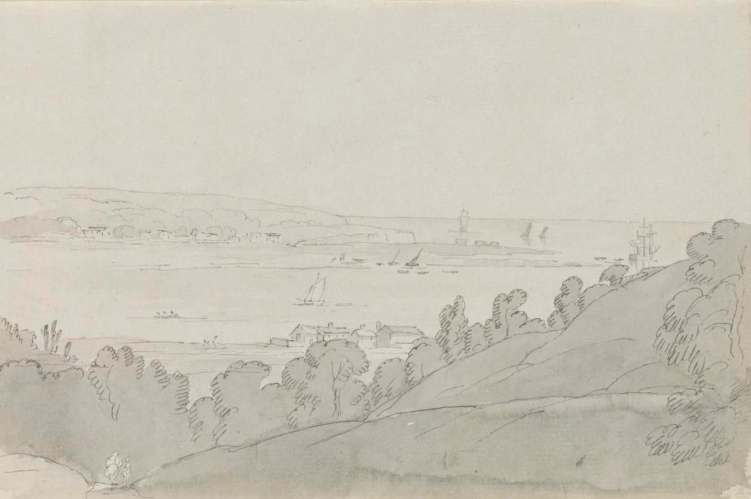

- John White Abbott (1764-1851), ‘Looking from above Starcross across the estuary of the river Exe’, pen and ink on paper, 1787. Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery.

- John Gendall (1790-1865), ‘Bicton | The seat of Lord Rolle‘, aquatint, ‘The repository of arts, literature, fashions, manufactures, &c‘. London 1 January 1825, page 1.

- John White Abbott (1764-1851), ‘Between Lympstone & Exmouth – Devon‘, 1802. Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery.

Page history

- 2024 April 12: first published online.

- 2024 April 14: extracts from letter of 15 May to John Pidsley added.

- 2024 April 27: ‘silk shirts’ amended to ‘linen shirts’.